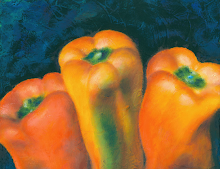

Oil on canvas

Oil on canvas20" x 16"

My contribution to the Art/Word show “Women of Influence.”

Janice was my drawing instructor at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 1977. I haven’t had any contact with her since then. I don't know where she is, or what kind of work she's doing, or even if she's still alive. This is a portrait of her as I imagined she would look some 30 years later.

Late in the first semester, she brought in some of her personal work to show to the class. From her guarded demeanor, you could tell that it was challenging for her to reveal and talk freely about her own art. I remember in particular a series of color photos she had taken, printed, and matted, each featuring a single raw egg yolk pierced by a dart. She called it her "egg-and-dart" series. Years later, I found out that "egg-and-dart" typically refers to a style of carved moldings comprised of alternating ovals and triangles, often found along the top of supporting columns in classical architecture, I imagine that she had heard the term during some lecture about ancient at, and that for her it came to suggest this other, more literal meaning.

I enjoyed the class. We drew from live models, including a woman who looked like she weighed 300 pounds or more, dressed only in a headscarf and banging out blues tunes on a guitar. Janice also had us draw a live mountain lion cub, a Guernsey cow, and each other's hands and feet. She taught us not to worry if we were middle-class; artists, she said, often came from the middle class, while the poor were too busy struggling to survive and the rich weren't looking for ways to work any harder. She taught us the being an artist, thought it could be rewarding, was not going to be a picnic; the world was not clamoring for more artists. (Clearly, she was also one to feel that artists needn't waste time worrying about whether their clothes were in fashion, although she didn't say so.) She told us to always sign our work, no matter how insignificant we thought it was. (I sign mine on the back.)

It seemed to me that, to an extent, she allowed her clothing and haircut to obscure her, and I have tried to convey this quality of her being hidden in plain sight.